A few days ago I wrote a post about the inherent problems of walk forward analysis (WFA) and why this technique – in itself – does not constitute a holy grail for automated trading. Since this post I have done deeper research into the matter and – by comparing results for several systems – I have been able to find interesting relationships between the number of degrees of freedom and the survivability in walk forward analysis (using simple selection algorithms). Within this post I will expand on this topic, attempting to explain why systems that are given more freedom are able to exercise a better ability to adapt and why this ability causes fundamental problems that lead to unprofitable walk forward analysis. I will also go into why this tells us something fundamental about the inability of systems to evolve towards unknown market conditions and how we may possibly deal with this.

As I went deeper into the area of walk forward analysis, it soon became clear that systems with successful WFA results have some very clear characteristics in common. The first obvious relationship between them was a very simple trading strategy setup, a higher trading frequency and a low number of possible parameter selections. Upon a closer analysis of the results it became clear that these systems were not changing dramatically over the course of the WFA but they were simply having small changes across a wide variety of market conditions. A closer look also revealed that the systems that give profitable WFA results tend to work only on pairs for which the inefficiency they trade seems to be practically ever-present, only failing under very specific market conditions and for short periods of time.

–

–

The above is important because it spoke to me about a general lack of adaptability. What we have here are systems that trade in a very fixed way – like a volatility breakout strategy does for example – and the ability to survive the WFA comes from the fact that the efficiency exploited by the system changes little across the instrument it is trading. For example volatility breakout systems will find very profitable results in symbols like the EUR/USD but they will fail bluntly on symbols where this inefficiency is not ever-present , such as the USD/JPY. More clearly, these systems will be unable to fend periods when the market has changed, for example in the case of the GBP/USD after 2009, where the market changed to make volatility breakouts almost obsolete. Although WFA may show reduced drawdown such periods, it does become clear that the drawdown in itself is unavoidable and if lasted long enough it would potentially destroy the account. If a good ability to adapt was present, the drawdown would have been easily avoided at least after the first part of the drawdown period made changing market conditions evident. A system that adapts to changing market conditions should easily avoid drawdown periods longer than a few WFA window lengths, especially if there is a complete and dramatic market change.

buy cytotec without a percsription In my view, it would be foolish to believe that such systems are truly adapting, because they never need to adapt to a dramatic change that removes the inefficiency they trade from the market and when they have to, they fail. However this poses a big question which is how we can give a system a larger ability to adapt in order to see if it can truly tackle dramatic changes in market conditions. At this point I decided to try systems with larger degrees of freedom, especially those systems that could generate dramatic adaptations to changes in market behaviour. The most obvious initial test is to try a system that can “switch” the way in which it trades in a very dramatic manner; a breakout strategy that can either fade or trade breakouts.

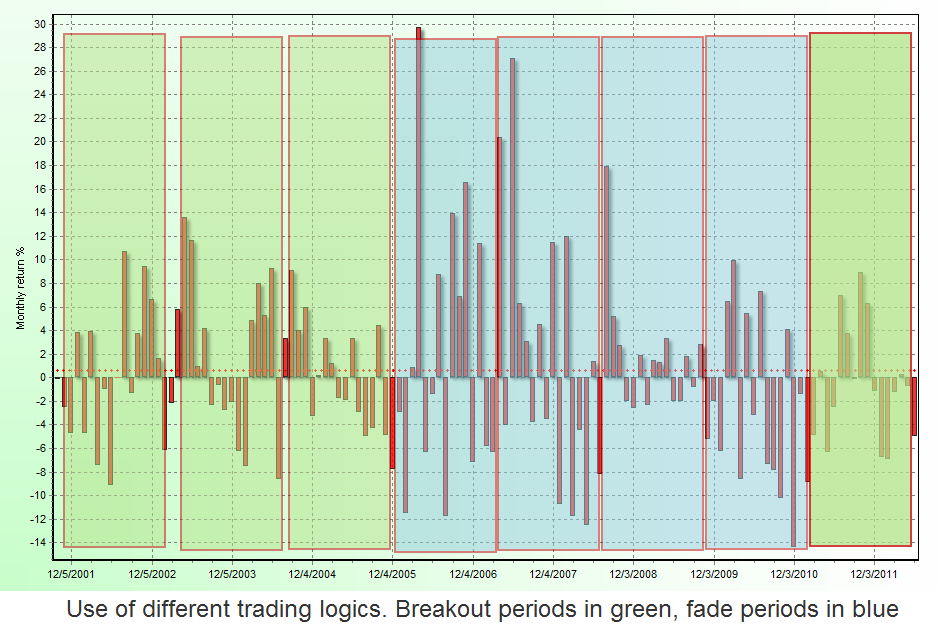

The results of this experiment were very interesting because they showed that under competing opposite market strategies there are optimization periods where both can give profitable results but only one gives profitable results in the subsequent walk forward trading period. However there were also times when one of the two system switches was dominant, achieving profitable trading through several different periods at a time, only failing when the other strategy started to become dominant. In essence what we have when we introduce freedom that allows for a completely different trading logic to enter the picture is a system that is “split” in duality between what it can achieve through both trading techniques. Such a system has enough freedom to adapt to two opposing inefficiencies and it only fails when the ground is neutral between the two (as the result is equivalent to a guess since none of the two techniques is dominant).

Perhaps the most dramatic effect is that the trading logic in fact changes in periods where you would expect it to, as the breakout inefficiency becomes less effective, the fadeout inefficiency becomes more predominant and the system starts to trade in a completely opposing manner. This is alike what traders generally call the “switch” a flip between two opposing market views that happens under changing market conditions. Clearly you have losing periods while this happens – while the change takes place – but if the change is long lasting you actually get a few periods of very good profitability. Obviously if the change is short lasting you hesitate between the two logics and you end up with drawdown accumulated on either case. The market is very efficient in this case because it fails to imitate its past behaviour.

–

–

The above is only the beginning of the story but it does show that walk forward analysis success only seems to make sense when you give your system enough freedom to completely change the way in which it’s trading. Using WFA to adapt a system that is “stuck” in a box is not a good idea because you’re fooling yourself into thinking you have a true ability to adapt to market changes when you are simply observing a positive effect because the inefficiency you want to trade is practically constant under the pair you’re analysing. By giving your system the ability to tap into logic that trades in a naturally opposing manner you ensure that you give your system the “ultimate choice” regarding the way in which it should be trading.

Granted, the above is not easy to achieve and you will see that WFA fails bluntly under many different conditions when you increase degrees of freedom. However, profitable WFA is indeed possible for systems with very complex makeups (even genetic frameworks) but we will get into this topic on future posts. If you would like to learn more about trading systems and how you can learn to trade and analyse them please consider joining Asirikuy.com, a website filled with educational videos, trading systems, development and a sound, honest and transparent approach towards automated trading in general . I hope you enjoyed this article ! :o)

Hi Daniel,

quite interesting findings. What I have learned so far is that there is no alternative to being able to “forecast” to some extent what will happen in the near future. WFA is based on the assumption that the recent past has some predictive power for the near future. If this assumption is wrong, WFA will not help you. In fact you might be better of using all of your available data to find a reasonable compromise which fits various market periods.

Best regards,

Fd

Hiya Daniel,

Wow this is an eye opener. It gives me an idea for adapting what strategy we play on the market:

So, we have 2 strategies – breakout and fade. In theory, when one wins the other loses, and we want to adapt what strategy we play on the market. I’m thinking that instead of a dramatic switch from one to the other, we do it gradually.

So, backtest both strategies to the current day and draw a moving average on the resulting balance graph. Take the gradient of that moving average and use that to set the risk% setting of BOTH strategies

– If they are both > 0, then play BOTH strategies on the market and set the risk setting to reward/punish each one fairly (eg. if the breakout strategy MA of balance gradient is 3 and the fade strategy balance gradient is 1, then set breakout risk to 0.75 and the fade risk to 0.25).

– If they are both < 0 then don't trade either of them (ie. breakout and fade strategies are currently unprofitable).

– If the gradient is 0 and the other strategies’ gradient fade -> breakout as we see the market change from the effect it has on our balance. I haven’t thought this through properly, it just popped up in my head after reading this blog post.

Btw I love your recent posts here. Welcome back to full time trading – really looking forward the developments in Asirikuy over the next few months :)

Mun

My comment didn’t come out correctly.. i think there is a bug in the website because the less than symbol caused my comment to get messed up

The last part was supposed to say:

– If the gradient > 0 and the other strategies’ gradient is less than 0, then scale the risk% of the profitable strategy by a factor of some normalisation of the gradient.

Doing it this way will give a gradual changeover from breakout -> fade -> breakout as we see the market change from the effect it has on our balance. I haven’t thought this through properly, it just popped up in my head after reading this blog post.

Hi Mun,

Thanks a lot for your comment and welcome message :o) I am also glad to be back to full time trading!

About your idea, I have to say that this is the first impulse – to take deterministic steps based on measurements based on past performance (balance changes) – but this doesn’t work. You can test it through both Monte Carlos simulations and system simulations and you will see that this mechanism – based on measurements of the balance such as moving averages, gradients, etc – falls short because you’re using a static decision system.

The best solution – at least the best one I’ve found up until now – is to introduce randomness to some extent, as game theory teaches us is the best way to deal with this. In any case, this will be covered on future posts :o) Thanks again for commenting (and please keep them coming!),

Best Regards,

Daniel

Hi Daniel,

I have noticed the exact same results with WFA. It is quite frustrating when you have a balance curve where the last few years are an inverse of the first trading years. But at the end of the day WFA is the TRUE performance of an expert advisor so it shows that the EA indeed cannot trade in certain market conditions.

It might be a good idea to change our expert building philosophy in the future if we struggle to find good WFA portfolios with our current systems

Hi Franco,

Thank you for your post :o) I think you’re putting too much faith on WFA. It is no holy grail and it is not necessarily an indication of the “true performance” of a trading system. The WFA analysis – as pointed by Fd – works when the assumption that the immediate past matches the immediate future is true, if it isn’t then optimizing for wide variety of conditions – to find a compromise – is the best solution. In my opinion, WFA is just a tool that works under certain circumstances but it is in no way the “best and only way” to do things. Some systems – for example – work well if you optimize them from 1990-2000 and then run them from 2000-2012 but they fail if you do a year-by-year WFA. It all depends on the system you’re trading.

I know, we now know nothing about this whole universe – we are just scratching a few things – so once we can test more advanced selection algorithms in the F4 strategy tester we will have a much better idea. By the way, it is also interesting to note that systems that have profitable WFA tend to have stable rank analysis (9/3) sets. Systems that fail to give stable sets never have positive WFA results (with simple selection algorithms). In any case, we’re – as always – open to what the evidence tells us, right now the evidence doesn’t say that WFA is the solution or that 9/3 analysis doesn’t work for all systems. It’s always telling us that WFA is sometimes an illusion of adaptability, so profitable WFA can be deceiving (you can believe it’s a source of additional robustness when it’s not because variations in market conditions have been subtle).

In any case, saying WFA is the “true” performance of a system is an over-simplification, the same as saying that 9/3 analysis doesn’t work or that everything should be done using WFA. We need to test and learn. Thanks again for posting your comment,

Best Regards,

Daniel